To Port, or Not to Port?

Suppose you have cancer and you are about to start IV chemotherapy. In that case, your oncologist may have given you the option to have a central line, such as a port-a-cath or a PICC line implanted — depending on the duration of your treatment.

Port-a-caths, commonly called ports, are a type of central venous catheter used for the longer-term transmittal of intravenous medicines. In contrast, PICC line, which stands for peripherally inserted central catheters, are intended for shorter time frames, usually weeks long.1,2

For many people with cancer, ports are often the preferred choice for a number of reasons.

What is a port?

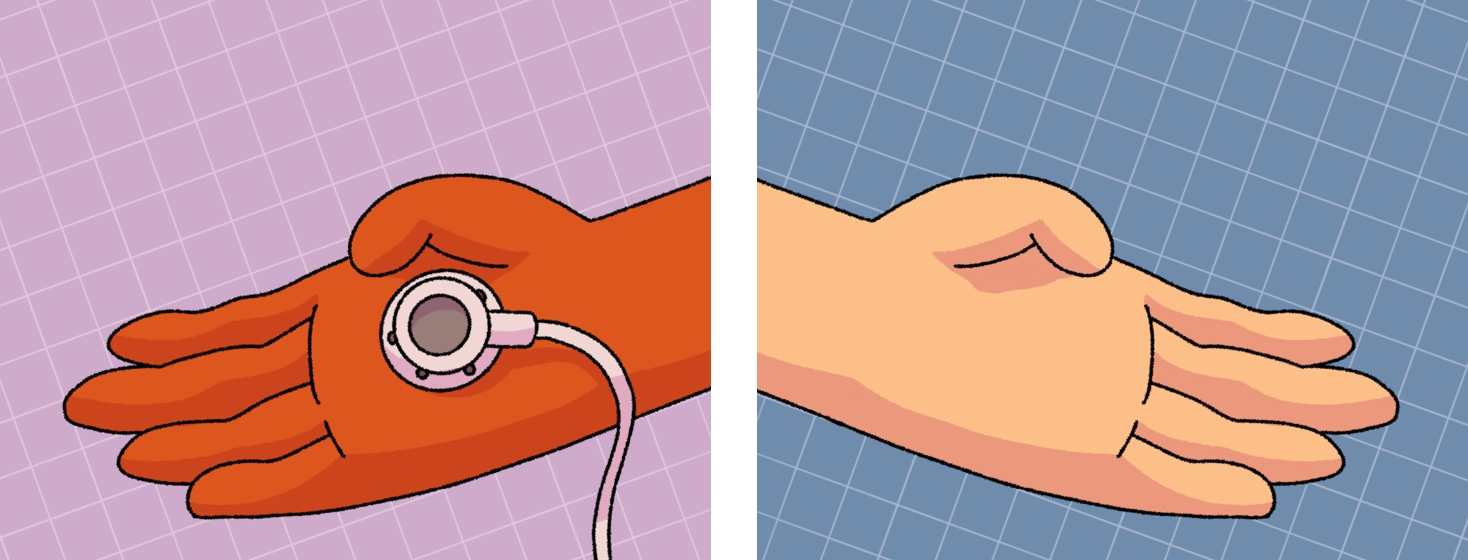

A port is a small medical device implanted beneath the skin of the chest, usually on the upper right side, approximately one inch below the collarbone. A thin, flexible tube called a catheter connects the port to a large blood vessel leading to your heart, also known as the superior vena cava.1,3

This can then be accessed for blood draws and giving intravenous fluids such as blood transfusions, chemotherapy treatment, antibiotics, and IV nutrients (also known as parenteral nutrition or PN).1

In order to access the port, my nurse would pierce a special needle through the skin into the port's center. This access point is approximately the size of a quarter. It feels like a round or triangular, raised bump under the skin and is made with a self-sealing rubber material that safely holds the needle in place while an IV or syringe is accessing it.

What are the benefits?

In my experience, ports allow patients more freedom and a greater sense of normalcy in their day-to-day lives. Once the port is placed and the area has healed, people can typically go about their regular daily activities like working, exercising, showering, bathing, and even swimming. Talk to your doctor first if you have any concerns.

Since chemotherapy can be particularly rough on veins, ports are intended to protect your veins during treatment. Certain medicines can even leak and burst or burn the smaller veins in one's arm. But since the port empties into a large vein, it helps avoid these types of complications.3

Ports can also help protect veins from damage caused by repeated access for infusions and drawing blood samples, which can become more difficult as treatment progresses. This is particularly recommended for those with smaller veins, which often need multiple pokes to successfully access an IV. A port is generally very visible to nurses and easily felt — resulting in safer and more efficient access.3

Lastly, accessing a port is less painful and reduces the risk of bruising or bleeding, especially if you have a low platelet count, and significantly decreases your chances of infection.3

What are the risks or concerns?

All types of catheters have their own side effects and complications, including potential blockages, thrombosis (blood clots), mechanical failure (i.e., separation of the port from the skin), or infection (although this risk is relatively low). Less common risks include catheter twisting, damage to the port (i.e., cracking), or the port moving or dislodging. But keep in mind these are rare occurrences.3

At the end of the day, deciding to get a port isn't always an easy decision. After all, having a port placed is a surgical procedure that requires local anesthesia. This can also result in permanent scarring, which can sometimes be an upsetting reminder of our cancer experience.

My port experience

Most people are concerned about the required aftercare and maintenance of having a port placed. For instance, ports require flushing after each treatment, as well as every 4 to 6 weeks when not in use to prevent blockages. While ports can be permanent and accessed as long as needed, many people have their ports removed shortly after finishing treatment. However, I admittedly grew somewhat attached to mine.4

Despite finishing treatment after 6 rounds of carbo/taxol chemotherapy over 18 weeks, I ended up keeping my port in place for nearly 3 years.

In all honesty, I held onto my port for so long because I am all too familiar with the statistics behind an advanced ovarian cancer diagnosis — particularly the likelihood of recurrence. I didn't want to have my port removed only to need to have it implanted again for further treatment.

Eventually, I decided it was time to "move on" and have my port removed, which was a relatively quick and easy procedure. Luckily, I had an extremely positive experience with my port, and I truly felt that it was the best option for me, but each person and scenario is different.

Ultimately, you must consider your own personal list of pros and cons and discuss this with your doctor to decide which option is best.

Join the conversation